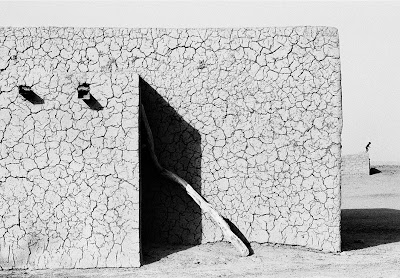

For

centuries, complex and intricate adobe structures, have been built in the

Sahal region of western Africa, including the countries of Mali, Niger,

Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Ghana, and Burkina Faso. Made of earth mixed with water,

these ephemeral buildings display a remarkable diversity of form, human

ingenuity, and originality.

In

a fascinating book, published in 2003, titled ‘Butabu: Adobe Architecture of

West Africa’, and co-authored by British photographer James Morris and

Harvard professor Suzanne Preston Blier, a stunning visual array of these

structures is displayed.

In

his Preface to the book, Morris writes:

“Too

often, when people in the West think of African architecture, they perceive

nothing more than a mud hut —a primitive vernacular remembered from an old

Tarzan movie. Why this ignorance to the richness of West African buildings? Possibly

it is because the great dynastic civilizations of the region were already in

decline when the European colonizers first exposed these cultures to the West. Being

built of mud, many older buildings had already been lost, unlike the stone or

brick buildings of other ancient cultures. Or possibly this lack of awareness

is because the buildings are just too strange, too foreign to have been easily

appreciated by outsiders. Often they more closely resemble huge monolithic

sculptures or ceramic pots than “architecture” as we think of it. But in fact

these buildings are neither “historic monuments” in the classic sense, nor as

culturally remote as they may initially appear. They share many qualities—such

as sustainability, sculptural beauty, and community participation in their

conception—now valued in Western architectural thinking. Though part of long

traditions and ancient cultures, they are at the same time contemporary

structures serving a current purpose.

The

mud from which these buildings are made is itself a controversial substance

that tests our conventional views of architecture. It is one of the most

commonly used building materials in the world, and yet in our urban-dominated

society it is seen, effectively, as dirt. Buildings subtly alter in appearance

each time they are re-rendered, which can be as often as once a year. Yet the

maintaining and resurfacing of buildings is part of the rhythm of life; there

is an ongoing and active participation in their continuing existence. If they

lost their relevance and were neglected, they would collapse. This is not a

museum culture…”

In

this review of the book from The Guardian Newspaper, journalist Jonathan Glancey writes:

“What

these magnificent mosques prove is that mud buildings can be far more

sophisticated than many people living in a world of concrete and steel might

want to believe. Mud is not just a material for shaping pots, but for temples,

palaces and even, as so many west African towns demonstrate, the framing of

entire communities. The very fluidity, or viscosity, of the material allows the

architects who use it to create dynamic and sensual forms.

Morris’s

photographic trips through the region in 1999 and 2000 record a world of

architecture that, sadly, is increasingly under threat. Perhaps it is mostly

poverty rather than culture and memory that keeps this rich and inventive

tradition of building alive…”

This

book is a treasure trove of imagery and information to any architecture

enthusiast. Critical elements like space, light, and texture are explored

in intimate detail, revealing a strong argument for this kind of architecture

to be studied, documented, and profiled more wildly. As Morris sums

up his preface: “I am still curious why West Africa’s adobe buildings receive

so little serious consideration. If architecture is a cultural expression,

perhaps it is the culture from which these buildings have evolved, so alien to

the European mind, that keeps it in the academic wilderness, hard for the

commentators to place.

+it+was+gradually+abandoned+after+the+Yuan+Dynasty,+the+fourteenth+century.jpg)

![Terra [In]cognita project: Earthen architecture in Europe](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjIS5lNr8tO_b1BIAUxQ7yOk-fWtBc-FOHi46AK7z5ExhggwlbKr1PYY6WxDega-Jey3Gc5tVPqpfmw8v-uiG8VWsXYWoBV7mPNsTfnEZ9HICEYXZwTmBQT1fbxZ0D0nR5b153SjGCFhk4/s285/logoterraincognita.jpg)